Hot on the heels of the landmark Australian Federal Court decision in July 2021 (discussed in a previous article here), the case of the artificial intelligence (AI) inventor has reached New Zealand shores.

Background

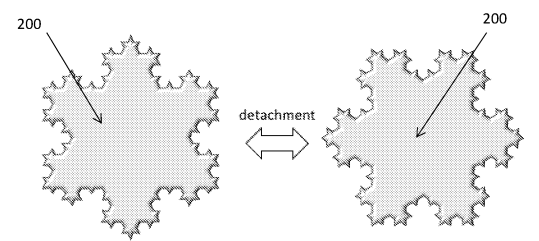

Dr Stephen Thaler, a scientist from the US, developed an AI system dubbed ‘DABUS’ - the Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience. DABUS can purportedly create new inventions and art forms, and has devised the claimed inventions, one of which is a food or beverage container with a fractal profiled flexible wall. The fractal profile of the wall supposedly permits multiple containers to be coupled together, and the flexibility of the wall allows for the decoupling of joined containers, as shown in the figure below reproduced from the patent application[1].

Dr Thaler filed several patent applications seeking to protect the claimed invention in many different jurisdictions. The patent applications list himself as the applicant, but DABUS as the inventor. This is because Dr Thaler asserts that DABUS created the claimed inventions, and thus it should be listed as the inventor on corresponding patent applications which seek to protect them. Dr Thaler has been using these patent applications as a test case as to whether an AI can be, or should be, recognised as an inventor under the patent system.

The patent applications filed by Dr Thaler have been subsequently rejected in multiple jurisdictions across the globe. The US, the UK, Germany, and Europe have come to the same conclusion, in that an inventor for the purposes of assigning patent rights, must be a natural person (i.e. an individual human being, as opposed to a legal person). Because DABUS is not a natural person, it follows that it cannot be validly named as an inventor of an invention as claimed in a patent in these jurisdictions.

Interestingly, in Australia the Federal Court came to a different conclusion. They found that there was nothing in the Australian Patents Act which “exclude[d] an inventor from being a non-human artificial intelligence device or system.”[2]

The Federal Court Judge accepted Dr Thaler’s arguments that the word ‘inventor’ as used in the Australian Patents Act 1990 should not be limited to individual human beings. The Judge explained that as “inventor” is not defined in the Act or Regulations, it must take its ordinary meaning. The Judge outlined that the word “inventor” is an agent noun, and as such, the agent can be a person or a thing. The Judge used the examples of the terms “computer”, “controller”, “regulator”, “distributor”, “collector”, “lawnmower” and “dishwasher” which are all similar agent nouns, and which apply to both persons or things. Accordingly, the Judge stated, ‘if an artificial intelligence system is the agent which invents, it can be described as an “inventor”’.[3]

The reason for this broad interpretation of the word “inventor” as used in the Australian Patents Act boils down to the overall purpose of the Australian Patent System, which is the promotion of technological innovation. The Judge outlined that ‘computer inventorship would incentivise the development by computer scientists of creative machines, and also the development by others of the facilitation and use of the output of such machines, leading to new scientific advantages’[4]

The New Zealand decision

In their decision released in late January 2022, the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (IPONZ) rejected Dr Thaler’s patent application naming DABUS as the inventor. In line with the US, Europe, and UK findings, the Assistant Commissioner in New Zealand determined that DABUS cannot be considered an inventor under the New Zealand Patents Act because it is not a natural person[5].

In this case (and as opposed to that in Australia), the term ‘inventor’ is defined in the New Zealand Patents Act 2013, in Section 5. This definition does not limit to an individual, merely requiring an inventor to be “the actual deviser of the invention.”[6]

Several other parts of the Patents Act do refer to an inventor specifically as a ‘person’ however, such as in Sections 3, 22, 177, and subpart 7 of the Act. The patent examiner picked this up and argued that these instances in the Act are a clear reference to the inventor being a natural person, which establishes the general interpretation that any mention of “inventor” in the Act refers to a natural human person.[7]

Dr Thaler’s arguments revolved around DABUS being the sole creator or deviser of the invention. He argued that, DABUS falls within the definition of an inventor set out in Section 5.[8] Thaler argued that those Sections of the Act, which refer to a ‘person’ who is the inventor are not applicable in the circumstances where the inventor is not a person.[9]

The Assistant Commissioner considered the approach taken by the Federal Court in the corresponding Australian case, but ultimately found that “the [New Zealand Patents] Act was drafted, and has always been applied, on the assumption that an “inventor” is a human being… Several sections of the Act do explicitly refer to the inventor as being a human being, and in those sections which do not, a consistent reading is incompatible with the inventor being non-human. The term “inventor” as used in the Act refers only to a natural person, an individual.”.[10]

The Assistant Commissioner noted that “a machine, and in particular a machine that functions as an artificial intelligence, is not a person under the law and is not a person as referred to in the Act. All the authorities agree on this. To be clear, the applicant has not asserted that DABUS is a person”.[11]

Ultimately, the Assistant Commissioner found that DABUS is not a person, and so cannot be “an actual devisor of the invention” or inventor under the Act.[12]

Is this the end of DABUS as an inventor?

Almost all the cases in corresponding jurisdictions have been appealed to a higher authority by Dr Thaler, so it seems likely that Dr Thaler will appeal this IPONZ decision to the High Court.

The Australian case has been appealed, and the Full Federal Court heard this appeal case on 9 February 2022. A decision should be released in the first half of this year.

We will continue to monitor these cases as they play out and report any further interesting updates.