2014 marked the year that the word “selfie” – for better or worse – was entered into the Oxford Dictionary. The earliest use of “selfie” appears to date back to 2002 [1] but increased dramatically between October 2012 and October 2013 – by over 17,000% according to Oxford Dictionaries.[2] For that reason, “selfie” was Oxford Dictionary’s “word of the year” in 2013, and in 2014 was further popularised by social media users, celebrities,[3] political figures, and even a photographing monkey.[4]

It may be no surprise then, that in December 2014, an invention called the “selfie stick” moved to the top of the Christmas gift list. Hundreds of thousands of selfie sticks have now been sold worldwide, with companies struggling to keep up with demand. One company reported an increase in sales of over 9,000% over the 2014 Christmas period – transforming the device from a rare piece of photography equipment into an everyday smart phone accessory.

Time Magazine even listed the selfie stick as one of 2014’s top 25 best inventions. So, who should receive the credit for all of this?

IP rights

A Canadian inventor, Wayne Fromm claims that the popularity of the selfie stick is the result of his inventive work in the past decade. In 2005, Fromm filed his US patent, number 7,684,694, which depicts his invention in the following way.

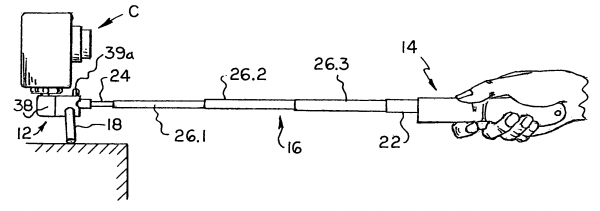

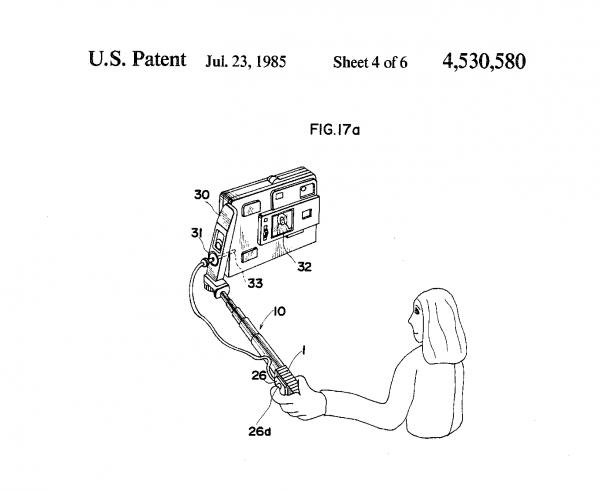

However, very similar devices have also been the subject of earlier patents, such as the following Japanese invention dating back to 1983 and patented in the US in 1985:

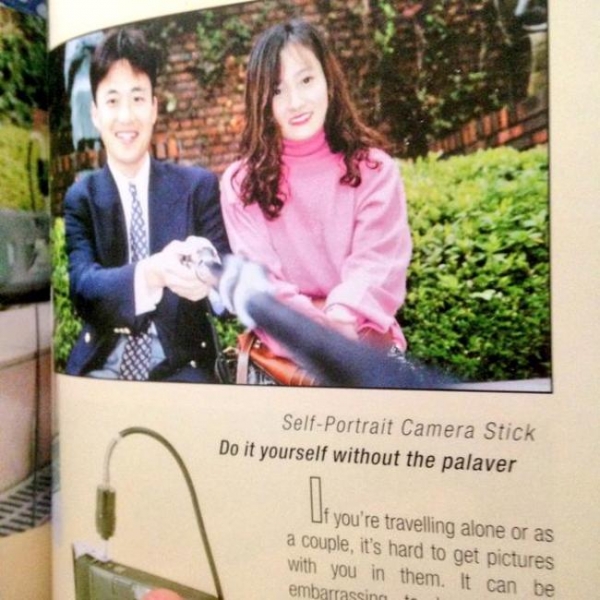

This image, also showing a selfie stick, appeared in a 1995 magazine of “un-useless Japanese inventions”:[5]

And then there’s this photograph, allegedly taken in 1925 and showing Arnold Hogg using what appears to be a selfie stick of sorts:[6]

So, while US patent holder Wayne Fromm claims that the popularity of the selfie stick is the result of his inventive work, there is much more to the picture than that. Fromm’s patent (which remains unchallenged for now) has not been used to prevent the sales of any other selfie sticks on the US market. It is likely that Fromm has now left it too late to do so, and has even acknowledged that any such attempts would be futile.

As an aside, potential trade mark rights in the terms “selfie” and “selfie stick” are also long-lost, now that they are widely and descriptively used. However, had the ‘inventor’ of the terms sought trade mark registration and/or maintained the terms’ exclusivity and distinctiveness, the words could potentially have been afforded trade mark protection – just like trade marks for other coined terms, such as “rollerblade” (in-line skates) and, more recently, “cronut” (pastry).[7]

Criticisms

Despite its popularity – or perhaps because of its popularity – the selfie stick is now on the receiving end of a reasonable amount of backlash. Several popular venues have banned the use of the sticks, and South Korean officials are apparently fining traders for selling selfie sticks that have not undergone adequate testing and registration before sale.[8]

Just last week, the London National Museum banned the stick, saying a ban had become necessary to protect artwork and visitors. Bans are apparently also in place at the Louvre in Paris, the Colosseum in Rome, the Smithsonian museums in Washington, and the Arsenal and Tottenham football stadiums in North London. The Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa, has confirmed that it encourages visitors to take photographs and that it does not intend to ban the stick unless it starts to cause problems.

On a different note, the major complaint in social media circles seems to be the overwhelming self-obsession with taking selfies, which ironically was a practice nourished by social media itself. Commentators have given the stick various nicknames, including the “narcisstick”. However, when we look at the selfie stick more objectively (absent the element of self-portraiture), all we are talking about is a tool for increasing the length of our arms or the reach of our fingers. As a species, we have been doing this for centuries – and as British photographer David Slater tells us, even monkeys reach for a gadget now and again.[9]

[1] Via ABC Online, an Australian Internet forum.

[2]http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2013/11/an-infographic-of-selfie/

[3] Most notably, Ellen Degeneres and Bradley Cooper at the 2014 Oscars – causing a fair amount of debate as to who would be the owner of the photograph.

[4] The monkey (see below) continues to cause controversy, with British photographer David Slater claiming that he owns copyright in the photograph taken by the monkey with his equipment, while Wikimedia refuses to remove the photos from its website, claiming that if anyone is to own the copyright, it would be the monkey. See, for example: http://consumerist.com/2014/12/15/photographer-still-trying-to-claim-ownership-of-monkey-selfie/

[5]101 un-useless Japanese inventions (1995), Kenji Kawakami.

[6] Alan Cleaver sent this photo of his grandparents, Arnold and Helen Hogg, to the BBC in December 2014.

[7]“Cronut” – the unlikely fusion of croissant and donut – has in fact been registered as a trade mark in New Zealand, and its owner, International Pastry Concepts LLC, is actively enforcing its rights.

[8] The law is said to be aimed at regulating Bluetooth and radio frequency transmission: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-30274974

[9] Photo credited to David Slater, 2014. Where copyright subsists, the above images are reproduced in accordance with section 42 of the New Zealand Copyright Act 1994: Fair dealing for the purposes of criticism, review, or reporting.